Based on the latest murderous rampage by the Russian impaler-in-chief, we wondered if humans are unique in their lust for killing their own kind. After all, what kind of animals are foolish enough to lay waste to those who resemble them?

The good news (or bad, depending how you view it) is that people are not alone in ripping one another to shreds. In a study by José María Gómez of the University of Granada, violence between humans can be attributed to our position on the evolutionary ladder. Mammals have a built-in thirst for their own blood, it seems.

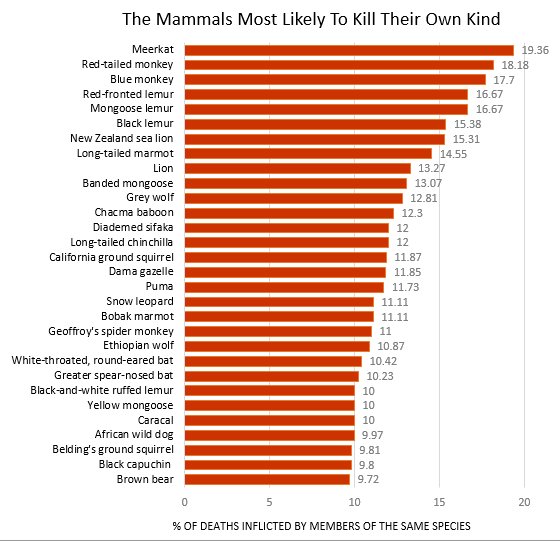

These days, the meerkat is the most savage of warm-blooded vertebrates, with about 20 percent of their deaths being chalked up to murder. One reason is that meerkat mothers kill the offspring of other females to maintain dominance (a favorite reason of autocrats as well). Also high on the list are the red-tailed monkey, the long-tailed marmot and the long-tailed chinchilla. Does Putin have a tail he’s not telling us about?

Yet humans can’t be found on this list. Between 500 and 3,000 years ago, we would have been at the very top, with up to 30 percent of people meeting their maker at the hand of their fellow sapiens. Now thanks to laws, cops, legal systems, prisons and social mores, less than 1 in 10,000 deaths is inflicted by the person next door (that’s .o1% for those doing the math).

So we are not as lethally violent toward our fellow man as meerkats are toward each other. But the Gomez study argues that over the course of human history, we are still more apt to commit murder than the average mammal.

Finally, a UK advertiser has pulled its campaign featuring a billionaire meerkat from the air in the wake of the Ukraine invasion. This has more to do with the meerkat in question being a cute, lovable Russian than it does to our comparison above. But it’s good to know what a meerkat is capable of. The same goes for dictators from Moscow. As Putin attempts to return “Mother Russia” to its former state, let’s hope the path forward doesn’t involve us all revisiting our mammalian roots from 3,000 years ago.