Hair is where painters show their biases towards design or nature, realism or abstraction. How a person paints hair reveals a lot about inner thinking and outer working process.

There are four main useful groupings revealing how artists think about hair (illustrated below.)

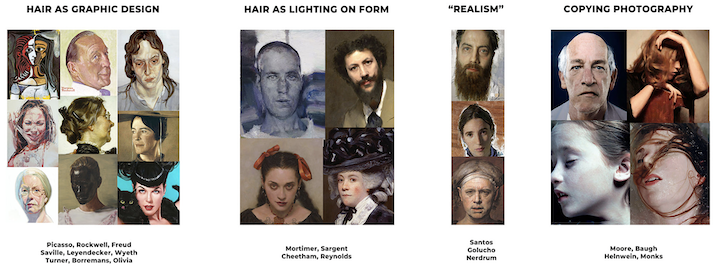

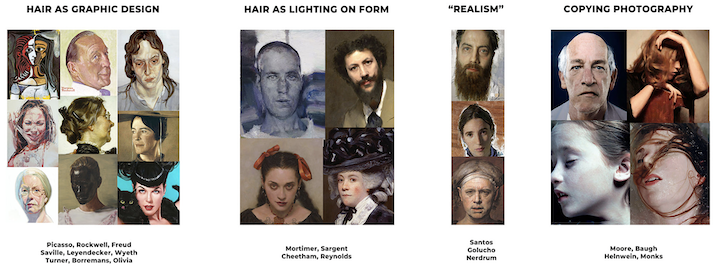

For some artists, especially painters coming from a background in illustration, hair is treated as a graphic design problem to solve. These artists seek ways to treat the tremendously complicated mass of hair as a simplified but intentional graphic design, often simplifying hair to strongly defined shapes and bold lines to execute hair as a graphic design. Examples include Picasso, Norman Rockwell, Lucian Freud, Jenny Saville, J.C. Leyendecker, Andy Wyeth, Ray Turner, Michael Borremans, and Olivia. This design-thinking is a very artistic approach but also a simple and minimalist mode, because illustrators need to get the job done and not spend hours fussing with hair. Once you have figured out a personal graphic-design way to interpret hair, the art can be done fast and effectively. But only after you know what graphic solution appeals to your taste.

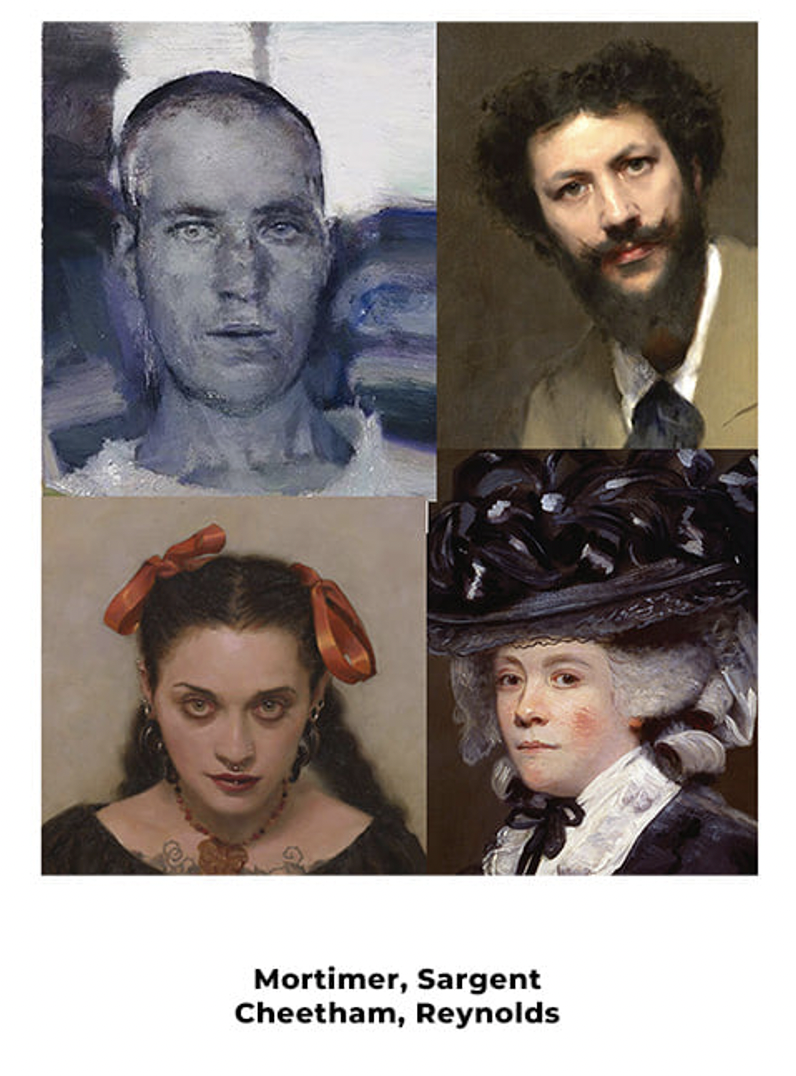

A second way to think about hair is primarily as lighting falling on semi-solid forms. This kind of distillation approach asks the artist to do two things. First, get the shapes (or outline) correct. Paint the shape with the right color and value to indicate believable lighting, shadows, highlights. This idea requires extracting a precise simplification of what we see, reducing the visual data, but if it is done with sophistication and practice, the results are what we typically consider “a good painting.” A clue that an artist is thinking this way is they will avoid unnecessary small details and not be painting any more individual hairs than strictly necessary, and “none” is ideal. Examples are Justin Mortimer, Sargent, Sean Cheetham, and Sir Joshua Reynolds.

A mild step away from that way of thinking is artists that like to build in some limited areas of crisply defined, intense realist hair details. This can look quite good as shown by Cesar Santos, Golucho, or Odd Nerdrum. These artists paint the overall hair as a mass but also feel that adding single hairs, single strands, areas of detail, and clean edges gives a more compelling illusion. The idea works to a point — but can become a flawed compulsion because we all know that this is not the way we perceive hair in ordinary reality.

Really? How do we perceive hair?

Have you ever found yourself seated with another person and begun to microscopically study any single hair on their head? Or an errant nose hair? Have you counted the lush hairs in their eyebrows? No. It is a misconception to think that we perceive reality in high-definition and high-resolution. We don’t. It’s not how human eyes and brains work. Paintings that attempt this greater fine-grained resolution typically look flat, stiff, or odd, and artists wonder why it doesn’t look artistically great when they sweat to paint every last pore and hair.

A fourth approach paints hair the way it appears in photographs. This dominant photographic aesthetic has contaminated art and our brains to the point that we approve of a very mechanical optical result. Most painters working from photographs try to deny the potentially poisonous influence of photography and say it’s just a valuable source of realist detail. There’s nothing morally wrong with choosing photography as your aesthetic goal as a painter, though if that’s what looks good to you it would be a lot easier to just use a camera and the results will be even better at feeling like a photograph. And 5000 times faster to accomplish. That said, some people do the style very well like Gottfried Helnwein. Casey Baugh, Alyssa Monks, and Michael Sydney Moore.